Finance and Governance

Enabling digital trade through legal reform

This article explains the benefits of digitalising international trade and analyses how the current legal obstacles mandating the use of paper-based documentation could be addressed through adopting the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records.

The case for digital trade

International trade is the engine that drives economic development around the world. Through trade, economies tap into one another to make up for shortfalls and address domestic demand for goods and services.

Economies have traded with each other since ancient times. Over the years, decades and centuries, driven by growing populations, economic outputs and – as a result – trade volumes, the means of trading internationally have evolved to address the increased demand. While the means of carrying goods across the borders have evolved, however, the practices and processes involved in the trade process have failed to follow suit. This is primarily because most trade processes still, at one point or another, require the production and exchange of paper-based documents to effect trade fully. This results in delays and inefficiencies. Digital technologies have the potential to deliver enormous benefits and transform the way (domestic and international) trade and trade finance work.

In the United Kingdom alone, using digital documents instead of the paper-based processes would improve the efficiency of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by 35 per cent, according to the International Chamber of Commerce. It would also reduce the number of processing days by 75 per cent and free up efficiency savings of £224 billion (€254 billion). Digitalising trade documents would generate £25 billion (€28 billion) in new economic growth for SMEs, together with £1 billion (€1.14 billion) in new trade finance.1

The Digital Container Shipping Association estimates that ocean carriers issue 16 million bills of lading a year, costing the industry US$ 11 billion (€10 billion) annually. Fewer than 0.3 per cent were electronic bills of lading. A 50 per cent adoption of electronic bills of lading would save more than US$ 4 billion (€3.6 billion) a year.2

Note: Figure depicts the Singapore/Rotterdam Corridor experience with an electronic bill of lading

Source: ICC France White Paper3 citing TradeTrust Newsletter issue 05 IMDA4

Trade documents and instruments

Trade and trade finance transactions are effected through the transfer and exchange of various documents and instruments such as bills of exchange, promissory notes, bills of lading, ship’s delivery orders, marine insurance policies, cargo insurance certificates and warehouse receipts.5 They create the necessary trust between the parties and mitigate the inherent risks of cross-border trade. The specifics of these documents vary, but the common feature they all share is that only the “holder/possessor” of such document/instrument can exercise the underlying rights that come with it.6

In international trade transactions, for the reasons mentioned above, parties transfer possession of such documents and instruments (together with their underlying rights) between each other. The legal concept of possession, however – in the vast majority of jurisdictions – comprises only physical possession of goods/things. This is the key element that dictates and mandates the physical production, transfer and exchange of such documents and instruments. As such it presents a barrier to the production, transfer and exchange of electronically issued documents and instruments.

The author would like to thank Gamze Kahyaoglu, Associate Banker, EBRD, and Andrei Mazur, Associate, EBRD, for their contributions to this article.

In the United Kingdom alone, digitalising trade documents would generate £25 billion in new economic growth for SMEs, together with £1 billion in new trade finance.

Legal and regulatory environment

Recognising that statutory reform of domestic legislation is the best way to remove the impediments arising from the legal requirements for “possession,” the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) prepared the Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records (MLETR). This law seeks to enable the legal use of electronic trade documents and instruments, both domestically and across borders.

In pursuit of this aim, the MLETR relies on the following principles:

- Non-discrimination against the use of electronic means – thus not allowing electronic trade documents and instruments to be deemed invalid solely on the grounds that they exist or are issued in electronic form.

- Functional equivalence – thus granting electronic trade documents and instruments the same status as paper-based counterparts.

- Technology neutrality – thus accommodating the use of all technologies and all models, such as registries, tokens and distributed ledgers.

Perhaps one of the key novelties under the MLETR is the introduction of the notion of “control” representing the functional equivalent of “possession” of a document or instrument. Under the model law, an electronic document/instrument meets the possession requirement if a reliable method is used to (a) establish exclusive control of that electronic transferable record by a person and (b) identify that person as the person in control. The MLETR also provides guidance on assessing the reliability of the method used to manage an electronic transferable record and on change of medium (electronic to paper and the reverse), among other things.

The digitalisation of trade documents would benefit many business areas, especially those that relate to transport and logistics. It also promises to facilitate access to credit, as it enables more innovative supply chain financing techniques (for example, deep-tier supply chain finance) that reach the SMEs in the deeper supply chain tiers.7 Furthermore, digitalising trade documents opens up opportunities for trade finance assets to become a liquid, investible asset class.8

On 1 February 2021, Singapore became the second country to adopt the MLETR principles when it amended its Electronic Transactions Act (ETA) by adopting the Electronic Transactions (Amendment) Bill (“Amended 2021 ETA”). The country did not fully adopt the text of the MLETR, but aligned its laws with MLETR provisions.9

Singapore has also taken practical steps to facilitate digital trade. The government has built a public Distributed Ledger Technology platform (TradeTrust) to support the exchange of electronic trade documents. It also proposed and is actively collaborating with the United Nations Centre for Trade Facilitation and Electronic Business to issue a white paper containing guidance on the transfer of MLETR-compliant titles.10

The first electronic bill of lading transaction governed by Singaporean law was issued in accordance with the Singapore ETA.

On 11 November 2021, Singapore’s Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), the Monetary Authority of Singapore and the Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Abu Dhabi Global Market, in collaboration with commercial partners, carried out the world’s first cross-border digital trade financing test transaction.11 The IMDA’s TradeTrust platform was used to transfer the electronic records between Singapore and Abu Dhabi. The pilot was made possible because both jurisdictions had aligned their laws with the MLETR.12

One of the key novelties under the Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records is the introduction of the notion of “control” representing the functional equivalent of “possession” of a document or instrument.

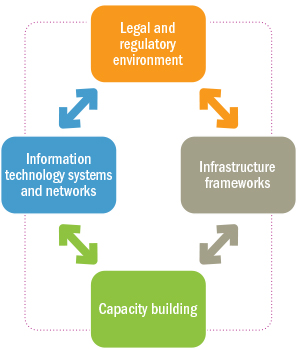

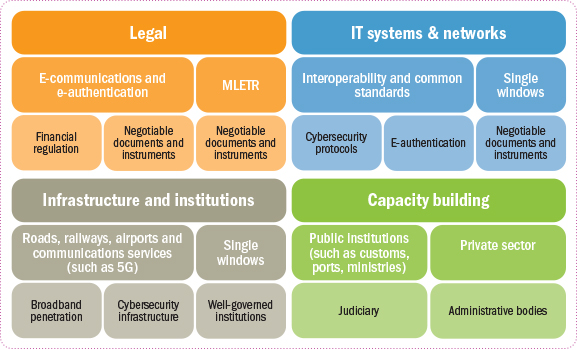

Building blocks for digital trade13

Numerous building blocks affect the uptake of digital trade. These are illustrated simply in the following diagram.

Source: Theodora A. Christou and John L. Taylor (2023), Blueprint Paper on Digital Trade and the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records. Available at: https://www.ebrd.com/documents/legal-reform/blueprint-paper-on-digital-trade.pdf, (last accessed on 19 September 2023).

Source: Theodora A. Christou and John L. Taylor (2023), Blueprint Paper on Digital Trade and the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records. Available at: https://www.ebrd.com/documents/legal-reform/blueprint-paper-on-digital-trade.pdf, (last accessed on 19 September 2023).

An enabling legal and regulatory environment that is conducive to digital trade is one of the main building blocks. We are aware, however, that three other – very important – building blocks need to complement the legal and regulatory aspect.

IT systems and networks that provide for safe and transparent interaction among all public and private actors involved in digital trade facilitate the electronic transmission and receipt of transferable records essential for digital trade. The IT platforms provide the (often sole) point of contact between public actors (port authorities, customs, tax and sometimes numerous government agencies) and private actors (the traders themselves, financial institutions, logistics, freight and shipping companies, and various service providers), each of which uses a range of IT solutions of their own. Interoperability between these different communication and transmission channels is essential for digital trade to work.

The broader infrastructure frameworks that should also be fit for purpose with the governments creating, and investing in, the necessary infrastructure and interconnector resources (such as roads, railways, ports, airports and communications services) that make it possible to carry out trade and trade finance digitally end-to-end.

Capacity building is an important building block which will improve awareness and build confidence in the digital environment. The upskilling of those engaging in trade, in both the private and public sector, will be necessary.

The Blueprint Paper on digital trade

The EBRD/CASTL Blueprint Paper on Digital Trade and the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records provides a comprehensive roadmap which governments can use in their quests to facilitate the uptake of digital trade through legal, regulatory and institutional reform. In the initial chapters, the paper sets out a clear case for paperless, digital trade by contrasting some of the inefficient paper-based trade processes that prevail worldwide with the much faster, simpler, more secure and environmentally friendly digital trade processes that modern technology offers.

The Blueprint Paper then examines the building blocks that underpin the transition to an end-to-end digital trade process. It identifies outdated legal and regulatory frameworks as one of the stumbling blocks to the uptake of digital trade and analyses how adopting the MLETR would address current issues. The paper summarises the efforts made by some countries that have reformed, or are in the process of reforming, their laws to align with the MLETR and provides – among other things – a “readiness matrix” that can be used to assess the level of alignment of local legal regimes with the MLETR.

The Blueprint Paper was presented and published at a public event on 25 April 2023. Click here to download the document.

The digitalisation of trade documents would benefit many business areas, especially those that relate to transport and logistics. It also promises to facilitate access to credit, as it enables more innovative supply chain financing techniques

The EBRD’s work on digital trade: Case studies

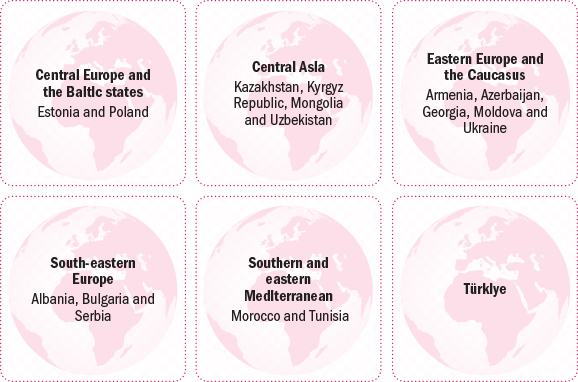

In line with the EBRD’s Strategic Capital Framework and country strategy priorities, the Bank is supporting a rapidly growing portfolio of digitalisation technical cooperation projects. These projects support a range of digitalisation initiatives to improve cross-border trade/logistics processes, enhance financial inclusion, promote cashless economy and support the development of an e-commerce sector.

Delivered between 2021 and 2023, this technical cooperation project aimed to support the Turkish Ministry of Trade with the design of a cross-institutional, end-to-end blockchain network that covered all stages of an export process, from the issuance of the initial receipt until the final transaction and the release of the goods from the Turkish customs/border.

The main focus of the project was to prove the feasibility of using blockchain in export processes and show the associated efficiency gains to the key decision-makers in Türkiye. To address this technical part, we analysed the current export processes and compared it to how such processes would work if they were migrated to blockchain and delivered via a blockchain-based platform. To demonstrate the feasibility and efficiency gains, we developed two demo blockchain platforms as proof of concepts (addressing exports of two different goods in two phases). Apart from the technical (IT-focused) components of the project, we also identified the legal and governance-related impediments that hinder the use of blockchain in the export process and provided recommendations for improvement. We are exploring the possibility to complement this “within-the-country” exercise with digital cross-border trade pilot implementation as the next step.

Since the Moldova-EU Association Agreement took effect in 2016 the Moldovan Customs Service (MCS) has been modernising its operating systems in line with EU requirements to enable customs administrations and traders to comply with international standards in import, export and transit-related procedures. To support these efforts, the Moldovan government asked for EBRD support to expand the operational capacity of the MCS’s ASYCUDAWorld system. The project Republic of Moldova: Support for the Digitisation of Custom Procedures is a package of four complementary assignments for the MCS and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry that are designed to help the government transition towards fully electronic customs procedures.

Expanding the ASYCUDAWorld system functionalities for MCS will help increase the speed and efficiency of customs clearance processes, facilitate e-commerce and cross-border trade, increase revenue receipts for the government, minimise the risk of consignment fraud and improve the efficiency of Moldovan customs operations. The project will also contribute to the government’s digitisation programme (eEconomy roadmap) and efforts to enhance transparency and efficiency in cross-border trade, reduce costs for businesses and help build resilience to the economic impacts of COVID-19. In addition, this new institutional arrangement should pave the way for better collaboration between the EBRD and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development to help address key transition challenges across the EBRD regions. The project is funded by the EBRD’s Shareholder’s Special Fund and EBRD – Türkiye cooperation fund.

EBRD support for non-performing loan resolution

The EBRD has been leading policy dialogue on non-performing loan (NPL) resolution with banks and banking regulators in its regions since the global financial crisis. Under the NPL chapter of the Vienna Initiative, the Legal Transition Programme has developed NPL resolution strategies for banking regulators in Hungary and Serbia to improve banking sector resilience. Recently our work has expanded to include legal reforms aimed at activating private NPL markets. With credit risks rising, now is a good time to take stock of recent NPL management best practices in Europe and beyond, and to develop effective strategies to reduce the accumulation of future NPLs.14

Background

NPLs are highly relevant for policymakers and have been in the spotlight for the last 15 years. NPLs occur when a borrower under a bank loan has defaulted by being overdue on principal or interest payments, or is unlikely to pay its credit obligations in full without recourse to actions such as the sale of any assets. There are divergences, however, in national definitions with respect to the period or timeframe when a defaulted loan qualifies as an NPL. In the EU, this period is usually 90 days from when the payment is past due.15

Further complexities arise with respect to NPLs owing to other relevant definitions. For instance, supervisory authorities refer to a broader definition of “non-performing exposures” (NPEs), introduced by the Basel Committee, to help supervisory authorities and banks adopt a consistent approach to monitoring and assessing banks’ asset quality. The NPE definition includes 90 days past due but also considers factors, such as forbearance measures, that would return an NPL to performing status.16 In addition, NPL specialists must contend with the prudential definition of “default” in the EU, which helps to ensure a sound identification of credit-impaired assets on bank balance sheets and enable banks to control risks and hold adequate capital, as well as the accounting definition of “impaired” (International Accounting Standard 39) for financial reporting purposes.

While the risk of non-performance is a part of every banking transaction, when those risks materialise and multiply, they can result in high volumes of NPLs in the banking sector. The consequences of high NPL volumes can then extend beyond the banking sector and have negative effects on the real economy. NPLs restrict the supply of fresh credit to businesses, reduce market confidence and slow economic growth.17 Evidence suggests that countries experience deeper and more protracted recessions when they do not act to contain the level of NPLs in the banking sector.18

NPLs trigger losses, which undermine bank profitability. Therefore, regulators typically require banks to provision against losses. A bank will estimate an expected future loss on the loan in its accounts and will use its capital to absorb these losses. In high volumes in a single bank, NPLs can even endanger the solvency of that bank, posing a risk to the entire financial system. Consequently, it is essential for both economic well-being and financial sector stability that financial regulators and banks take pre-emptive action to deal with NPLs. This means ensuring that effective legal and regulatory tools are in place to enable – and in some cases require – banks to address the NPL cycle. As part of this exercise, national authorities and policymakers can benefit from strategic technical cooperation offered by the EBRD and partner international organisations to improve their NPL resolution frameworks and underlying processes for managing NPLs.

Why are non-performing loans not increasing given the recent challenging economic conditions?

Many analysts and commentators predicted a rise in NPLs (and insolvencies) in response to the major economic shock caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, which led to a 2.4 per cent contraction in output across the EBRD regions in 2020.19 When this did not materialise immediately, there was an expectation that NPLs would increase in 2022. The war on Ukraine led to a surge in energy and food prices, driving inflation into the double digits for 80% of the economies where the EBRD invests.20 However, NPLs have remained low and the banking sector in many EBRD and European economies has proved to be largely resilient in the face of these challenges, with stronger capital buffers and regulatory safety valves and more profitable and liquid banks than at the time of the 2009 global financial crisis. Another factor preventing an increase in NPLs has been the unprecedented levels of emergency government assistance and liquidity, as well as the legislative and non-legislative moratoria (standstill) on loan repayments provided to businesses and consumers during the pandemic.

While many of the Covid-19 emergency support measures have been phased out, they unquestionably kept a number of weaker businesses artificially alive for a period.21 A 2022 survey by the EBRD LTP on NPL-related emergency measures introduced as a Covid-19 response in the EBRD regions revealed that 85 per cent of EBRD economies introduced temporary banking and tax related emergency measures to mitigate the negative impacts of the pandemic. Banking measures included capital injections, prohibitions on the payment of dividends to bank shareholders, grace periods for loan servicing for households and businesses (including full or partial relief from repaying loan principal), capitalisation of interest, prohibition on increasing interest rates, interest-rate subsidies and state credit guarantee programmes. Tax measures, on the other hand, covered temporary tax relief or reductions in personal and corporate income tax, in particular for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as the waiver of fines for late submission of tax declarations and late payment of taxes.22

It is essential for both economic well-being and financial sector stability that financial regulators and banks take pre-emptive action to deal with non-performing loans.

non-performing loans are declining in many countries

In Europe, NPLs have been on a downward trajectory since 2015, but credit risks are rising due to higher interest rates and a challenging business environment. In most countries where the EBRD invests, the stock of NPLs is low, with the notable exception of Ukraine, where the Russian invasion has wiped out the country’s success in recent years in reducing NPL levels.23 In the central, eastern and south-eastern Europe (CESEE) region, NPLs have continued to decline despite the Covid-19 crisis and the recent economic downturn. As of the third quarter of 2022, the average ratio of NPLs in the banking sector across the CESEE region, while higher than the EU average, was at a record low 2.5 per cent. Overall, this mirrors a decreasing trend in NPLs across Europe in the first half of 2022, which the European Banking Authority (EBA) attributed in large part to NPL securitisations and asset disposals in its November 2022 Financial Stability Review.24

In some countries, the decrease in NPL ratios in recent years has been remarkable. In Serbia, NPL levels dropped from about 20 per cent of total bank assets to about 3 per cent from 2012 to 2022. In Greece, on the other hand, where NPLs reached systemic levels after the 2007-08 global financial crisis, the government-sponsored NPL securitisation scheme appeared to have yielded positive results. As of the second quarter of 2022, the Greek NPL ratio stood at 5.2 per cent, with the Bank of Greece reporting a 40 per cent reduction in the corporate NPL ratio between June 2018 and June 2022.25

Nonetheless, there is an expectation that new NPL flows will increase across some EBRD economies in 2023 and 2024. This is in line with the trend in the central and eastern European region in relation to the accounting classification of “Stage 2 loans”, which rose by 0.95 per cent from 11.2 per cent in December 2021 to 12.15 per cent in December 2022.26 According to the International Accounting Standards Board’s International Financial Reporting Standard 9 on recognition and measurement of financial assets, these loans are not yet impaired (Stage 3) and are therefore not NPLs, but they are loans where the credit risk has increased significantly.27 As interest rates remain high and economic uncertainties linger, there is an expectation that some of these Stage 2 loans will deteriorate further, becoming Stage 3 non-performing exposures.

In Europe, non-performing loans have been on a downward trajectory since 2015, but credit risks are rising due to higher interest rates and a challenging business environment.

The Vienna Initiative has contributed to better crisis preparedness and countries are better prepared than during the global financial crisis

Despite increasing credit risks, many national banking regulators are better prepared to address and deter a rise in NPLs in the banking system than they were 10 years ago. The 2007-08 global financial crisis tested the resilience of financial institutions and the reactiveness of financial regulators across the world. It resulted in large levels of NPLs accumulating on banks’ balance sheets over the following years, as borrowers struggled to fulfil their original repayment obligations and threatened bank solvency as well as the financial system at large. Many countries turned to the IMF for assistance and loans, as the crisis spread and access to the financial markets became restricted.28 At the same time, many governments sought to safeguard their national banking systems by providing extensive liquidity measures to credit institutions. The global financial crisis and its aftermath had a severe impact on the regions where the EBRD invests and challenged the Bank’s core mandate of fostering the transition to well-functioning market economies in its regions of operations.29 However, it also galvanised regulators to action and boosted efforts to find both national and cross-border regulatory solutions.

In response to the global financial crisis, the EBRD launched the Vienna Initiative, together with the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB), the European Investment Bank, the EU, the IMF and the World Bank to help coordinate regulatory decision-making in emerging Europe and prevent a systemic banking crisis. By 2011, with significant deleveraging across the banking sector, the Vienna Initiative 2.0 was established and expanded to support national regulators with the resolution of NPLs in the banking sector to protect the countries’ economies and re-activate bank lending. At the end of 2014, a dedicated regional NPL initiative was created (as a subset of the broader Vienna Initiative 2.0), for the EBRD central and South-eastern Europe region. This initiative focused on resolving the high stock of NPLs in EBRD partner countries.30 Vienna Initiative 2.0 activities relating to NPLs continue to be relevant today, with regulators in the EBRD CESEE region meeting periodically to exchange ideas and best practices and consult, sharing the latest NPL information on the EBRD Vienna Initiative website, including the NPL Monitor – a biannual publication of the NPL initiative.

Following the global financial crisis, EU institutions have led a number of important legislative and regulatory initiatives in the NPL field. These have been a source of inspiration for national authorities in EU accession countries and beyond.

The 2017 EU non-performing loan Action Plan

In response to the threat to financial stability caused by NPLs in the EU, the European Council in 2017 approved an action plan to address the problem of accumulating NPLs in the banking sector. The plan outlined different policy actions to help reduce the stocks of NPLs and prevent their future emergence.

As part of this plan, the initial focus was on better understanding the scale of the NPL problem through the standardisation of bank financial reporting for comparability and supervisory assessment purposes. Regulatory scrutiny was on the accumulation of NPLs on banks’ balance sheets, for which multiple priorities were set, including ensuring the existence of adequate data on NPLs, improving NPL provisioning and defining the supervisory expectations from banks with regard to NPL management and prevention. EU authorities also placed strong emphasis on the further development of the EU secondary market for NPLs. Following the approval of the 2017 EU NPL Action Plan:

- The EBA developed voluntary NPL data templates for NPL sales to improve the standardisation of data in the EU and to facilitate the NPL transaction process.31

- The ECB developed provisioning calendars to accelerate provisioning with respect to NPL stocks for banks under its supervision. It also introduced possible (Pillar 2) implications for non-compliance. This was then further standardised and expanded to all EU credit institutions, with a provisioning backstop (that is, a Pillar 1 mechanism) in the EU Capital Requirements Regulation and applicable to exposures originated from 17 April 2019 and subsequently becoming non-performing.32

- Several EU policy and regulatory actions were introduced with the aim of improving the banks’ management of NPLs and preventing a future NPL build-up. These included (in order of delivery): the ECB’s Guidance to banks on NPL management,33 the EBA’s Guidelines on the management of non-performing and forborne exposures34 the EBA’s Guidelines on loan origination and monitoring,35 and additional NPL reporting and disclosure templates produced by the EBA.36

Following the global financial crisis, EU institutions have led a number of important legislative and regulatory initiatives in the non-performing loan field. These have been a source of inspiration for national authorities in EU accession countries and beyond.

The 2020 EU non-performing loan Action Plan

Another phase of NPL activity followed the pandemic. In December 2020 the European Commission published a new NPL action plan due to the Covid-19 crisis and expected rise in NPLs.37 Under the 2020 EU NPL Action Plan:

- In October 2022 the European Commission and members of its NPL Advisory Panel published a set of practical, non-binding guidelines on a best execution process for NPL sale transactions on secondary markets.38 These guidelines aim to fill a gap in relevant market experience and knowledge.

- The EBA produced new standardised and mandatory data templates, based on its previous (voluntary) 2018 templates. All EU credit institutions are now required to complete these templates and provide a certain minimum level of information to purchasers when selling NPLs.39 It is not entirely clear how the use of templates will be monitored from a banking supervisory perspective. Furthermore, it remains to be seen to what extent the templates will encourage banks to improve ex ante their data collection systems from the point of origination and their loan documentation.

In addition to these measures, the EU authorities published the 2021 Directive (EU) 2021/2167 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2021 on credit servicers and credit purchasers (the Credit Servicing Directive).40 This represents yet another important EU innovation in the NPL field, with its focus on the professional management of NPLs. In its initial form, the proposal adopted by the European Commission in March 2018 proved quite controversial as it also included a so-called accelerated enforcement mechanism. The mechanism recognised the effectiveness of out-of-court enforcement and sale for NPLs where contractually agreed between commercial parties, but was unpopular with a number of EU member states. In its current and final form, the directive focuses on harmonising the secondary markets for NPLs (consumer and business) and improving professional standards concerning the management of NPLs. For instance, the directive establishes certain requirements across the EU regarding the sale of NPLs to non-EU credit institutions and the activities undertaken by so-called credit servicers, which will require a licence to carry out their activities. The definition of credit servicing activities in the directive is broad and includes debt collection activities involving the collection or recovery from the borrower, in accordance with national law, of any payments due related to a creditor’s rights under a credit agreement or to the credit agreement itself. From previous studies in the consumer field, it is clear that there are gaps in the existing EU member state domestic legal and regulatory frameworks concerning the management of NPLs, including in the consumer sphere.41

It is widely expected that the Credit Servicing Directive will result in consolidation of the existing (fragmented) credit servicing market as only larger, more professional service firms will be able to afford to make the changes needed to comply with the increasing regulatory requirements in the industry. The deadline for the transposition of the directive is set for 29 December 2023. However, as of April 2023, only France had taken steps to align its legal framework with the provisions of the directive. For a discussion on current trends and an interview with a leading NPL industry professional, see page 62.

More recently, the EBA has published a consultation paper for draft guidelines to assess the knowledge and experience of the management or administrative body of a NPL credit servicer. The final form of these guidelines is expected to be published by the end of 2023 and enter into force from early 2024. The guidelines would constitute an important step for the implementation of the requirements of the Credit Servicing Directive.

In December 2020 the European Commission published a new non-performing loan action plan due to the Covid-19 crisis and expected rise in non-performing loans.

Ongoing challenges to non-performing loan resolution and non-performing loan resolution strategies

Banking regulators have a key role to play in setting NPL resolution strategies and ensuring that banks properly recognise their NPLs and provision for any potential losses. Nevertheless, while many national regulators seek to align with the standards proposed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision by the Bank for International Settlements, there is no universally accepted definition of NPLs or NPEs globally. Outside of the EU, the approach of different national regulators to various NPL-related matters can diverge greatly.

Since 2011, the EBRD’s LTP has led several country-specific NPL diagnostics and strategies in conjunction with EBRD economists and policymakers. These projects have included the provision of advice and country legal, tax, financial and regulatory analysis to the Hungarian National Bank, the National Bank of Serbia and the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency in Türkiye. Most recently, the EBRD has collaborated with the Agency for Regulation and Development of the Financial Market and the National Bank of the Republic of Kazakhstan (NBK) to develop a strategy and concept to create a market for distressed assets (see page 63).

Many common ongoing challenges remain to the development of NPL markets across EBRD economies, notwithstanding national differences. Broadly, these can be grouped under two main categories. The first is specific NPL resolution issues – in other words, the various strategies available to an NPL holder or purchaser to resolve or work through its NPLs. These include restructuring, compromising or postponing the loan maturities and voluntarily selling any underlying secured asset, collecting or enforcing the loan (whether unsecured or secured) and, in some cases, where all the forgoing are unsuccessful or where it cannot otherwise be avoided, insolvency. In many emerging markets and jurisdictions, and even in the EU, an NPL holder wishing to implement a resolution strategy faces major limitations and costs. These include high procedural requirements, such as in-court enforcement and mandatory public auction sale (especially for immovables such as land), advisory and long court processes for both enforcement and insolvency.42

The second category of challenges focuses on NPL market development issues, which determine the level of access and opportunities available to both a potential NPL seller, such as a bank, and an NPL purchaser or investor. These include matters such as market size and the potential volumes needed to attract professional investors, information quality and the availability of the necessary data for an investor to invest and/or to avoid a substantial discount, and macroeconomic factors such as the stability of the currency that have an impact on investor appetite. Moreover, the development of the NPL market depends on legislation and regulations, which often restrict the type of entity that may acquire a loan. It is common for NPLs to be transferable only to other domestically licensed banks, especially in the consumer sphere. In new NPL markets, there is always an additional level of uncertainty and unpredictability for an NPL investor. This can be exacerbated by the relative lack of local experience – for instance, in the local credit servicing industry. The right regulatory approach and market signals from regulators and targeted legal reforms can overcome some of these obstacles, however, providing opportunities for the international or regional investor. Furthermore, there is potential for the development of digital, cross-border solutions, including electronic platforms for the sale of distressed loans and related assets. Coupled with standardised information on NPLs, these may increase transparency for investors and, hopefully, investor participation.

Since 2011, the EBRD’s Legal Transition Programme has led several country-specific non-performing loan diagnostics and strategies in conjunction with EBRD economists and policymakers.

While the focus may have shifted to prevention rather than cure, support for the management of non-performing loans across the EBRD regions remains an important policy goal for the Bank.

While the focus may have shifted to prevention rather than cure, support for the management of NPLs across the EBRD regions remains an important policy goal for the Bank. The Vienna Initiative continues to be an active forum for regulators to convene and exchange information. This was the case in the 2020 regulatory response to the coronavirus and may be the case again, as credit risks materialise and NPLs follow their inevitable, cyclical increase. In this context, it is positive to note that the level of awareness and thinking on potential NPL solutions is high. There have been many new standards and ideas, including those emanating from regulators and national governments, such as Greece and Italy, in the EU. National regulators in the EBRD regions can consider and evaluate these different initiatives, as part of developing their own tailored approach and country strategy for the resolution and sale of NPLs.

Eric, what do you think are the most important current policy trends in NPL resolution?

The most relevant policy trends are, at least in the EU, around further improving and standardising the existing rules for sound NPL transactions, including rules related to credit purchasing and servicing, NPL data and NPL securitisation. There has also been a lot of discussion within the EU on harmonising the enforcement regimes and insolvency laws of different member states, but this will likely take time. We can also observe a very rapid evolution of policies around ESG themes, with increasing consideration of climate risks in NPL portfolio assessments and investment decisions. There is also a concern to ensure that NPL resolution is socially responsible. Further regulating the use of blockchain and crypto in the financial service industry is also relevant for advances in NPL transactions and securitisation. And artificial intelligence (AI) is very topical for credit management and NPL resolution – we can anticipate that AI policy discussions will develop in the coming years.

How are advisory firms like KPMG supporting clients on NPL matters?

Overall, firms like KPMG are providing a wide range of services to support their clients on NPL matters, helping them to navigate the complex and rapidly evolving landscape of distressed debt transactions and resolution. We provide advice on regulatory and compliance matters related to NPLs, as well as helping clients implement best practices for credit risks and NPL management. One of the key areas where KPMG operates is as a “sell” and “buy side” adviser to banks and investors, providing support on due diligence and loan portfolios structuring strategies. We also provide advisory services on NPL portfolio management, helping clients to develop strategies for managing their NPLs, including restructuring and workout plans, loan sales and securitisation. As a large advisory firm, KPMG has its own data management technology and data analytics to support NPL transactions and loan management.

How do NPL management standards compare with leading markets outside the EU, for example, North America and Asia?

While there are many similarities, I would say that the EU has a more structured and comprehensive framework for NPL management. In other markets, the approach is more decentralised and varies by country or regulator. This is partly due to how the EU, with its 27 countries, is structured, and the need to ensure harmonisation of rules and practices across member states. Over the last few years, significant progress has been made by EU regulators and supervisors in setting clear regulatory expectations with regard to how banks manage their credit risks and NPLs and close monitoring of bank compliance. We are also seeing an evolution in the regulatory approach within the EU to standardise credit purchasing and servicing. In my view, the EU is now leading on NPL policymaking globally and, consequently, we see a lot of interest from other countries to learn from what are considered as “EU best practices”.

How important will technology be for future NPL markets?

Technology is very important for the future of the NPL markets, and we have already witnessed fundamental changes in recent years. Looking forward, we can expect that the use of technology will further drive innovation, reduce costs, increase efficiency and improve the overall quality of NPL portfolio management. As technology continues to evolve, including with the broader and more mainstream use of AI and machine learning, we can only anticipate further (and significant) streamlining and automation across all aspects of NPL management and transactions. There has been a substantial growth in advanced analytics tools for portfolio assessment, data remediation, pricing and investment decisions. While not new, the role of online NPL marketplaces and platforms is likely to continue to increase, as new tools become available. However, due to the high level of tailoring needed during a live transaction, I expect that human involvement in the deals will remain necessary for some time.

What do you see happening at the EU level over the next few years?

In the next few years, we can expect continued innovation in NPL management and transaction practices, driven by technology and regulatory changes. However, the pace of the changes depends on the volume of new NPL flows. The lagging effects of the pandemic and the current macroeconomic and geopolitical environment are still yet to translate into more NPLs, and NPL levels have stabilised at a low NPL ratio of 1.8 per cent in the EU (EBA Risk Dashboard Q4 2022). Regulators are warning of residual risks related to the end of over a decade of very low interest rates – this makes a deterioration in asset quality and a rise in NPLs still likely. The evolution and duration of the war in Ukraine will also have an impact on the NPL environment. Only time will tell, but we can expect that the EU banking regulators and supervisors will continue to monitor the situation closely to avoid any new accumulation of NPLs in the European banking system. As a minimum, the ongoing regulatory activities related to NPLs will continue, including the implementation of the requirements of the European Commission Credit Servicing Directive on NPLs and the EBA NPL templates.43 We also expect a broad range of new regulatory initiatives in response to technological innovations and ESG, as discussed previously, which will shape the future of NPL markets.

In October 2020 the Agency for Regulation and Development of the Financial Market of the Republic of Kazakhstan (the Agency) and the NBK requested the EBRD’s assistance in promoting the sale and transfer of distressed assets in Kazakhstan to private investors. The first phase of the project, funded by the EBRD’s Special Shareholder Fund and the NBK, resulted in a legal, financial and regulatory analysis of the NPL landscape in Kazakhstan, benchmarked against EU best practices, and recommendations for opening the NPL market to domestic and international investors. In particular, the most important and urgent recommendations were to (1) expand the list of buyers that are authorised to purchase impaired loans in Kazakhstan and (2) establish a new regulated entity, and associated legal concept, of “credit servicer”. These recommendations were reflected in the law On Amendments and Additions to Certain Legislative Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan on the Development of the Market of Distressed Assets No. 133-VII, which was adopted by the government in July 2022 and came into effect in September 2022. The EBRD then followed up with further technical cooperation to the Agency and the NBK to support the alignment of the Agency’s regulations with ECB guidance to banks on the management of NPLs.

In January 2022 the president of Kazakhstan ordered the creation of a secondary market for banks’ distressed assets and tasked the Agency and the government with the establishment of a digital platform and the necessary infrastructure for the online sale of distressed assets. In response, the EBRD team began to develop a model for an electronic platform to sell NPLs and foreclosed assets and to stimulate the development of the private NPL sales market. The EBRD is finalising this model, tailored to the requirements of the Kazakh market. As part of this exercise, the working team led by the EBRD has developed data templates, aligned with the NPL data templates recently mandated by the EBA but with mandatory fields suitable for the Kazakh banking sector. It is expected that these data templates will be used, subject to some specific exceptions, for the sale of all impaired loans and foreclosed assets by Kazakh banks via the digital platform. The use of such data templates will improve the availability of information and the transparency of sales in Kazakhstan for potential investors.

Addressing the sectoral and corporate governance reform needs of state-owned enterprises: The EBRD approach

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) still play an important role in many economies in which the EBRD invests, especially in key industries such as energy, water, gas, road and railway infrastructure, railway transport and postal services, but also in sectors where the need for the state’s involvement is less obvious, including telecoms shipping and even manufacturing services.

Against a backdrop of ever-increasing complexities in global supply chains and a succession of crises such as Covid-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and spiralling inflation, SOEs have been an important source of stability in many developed and emerging economies. They have also been instrumental in maintaining the flow of essential goods and services to citizens and the economy. This is why, in recent years, international financial institutions including the EBRD have stepped up their focus on policy engagements with SOEs. While the core mandate of the Bank remains private sector development, increasing the quality of policy interventions with SOEs improves the investment climate and enables more private ownership.

In the past, SOEs were seen mainly as obstacles to economic development, especially when the state mandate extended into areas where the private sector proved to be much more efficient and innovative. Recent crises have revealed another side of SOEs’ function. For example, the climate crisis has shown that for renewable energy to scale up to the level required by the Paris Agreement, electricity networks must be able to manage the flows of energy – and those networks are state-owned in most countries. In the case of Ukraine, SOEs have been crucial in ensuring the flow of indispensable goods and services throughout the country, such as maintenance of electricity and transport networks that were, in some cases, badly damaged and by maintaining functioning of railway transport and postal services. Once the aggression ends, SOEs will be just as important in helping to rebuild the country.

While ensuring stability in matters such as energy and food security is paramount in the short term, we should not lose sight of the bigger picture: the need to achieve balanced and sustainable development and move the dial in terms of the reliability and quality of services of public interest. In parallel with providing finance for major infrastructure improvements, there is also a great need to advance the reforms in both the governance and sectoral legal frameworks as well as market structures. This provides a unique opportunity to combine sector-level reforms and improve the efficiency and capacity of SOEs involved in those sectors.

In parallel with providing finance for major infrastructure improvements, there is also a great need to advance the reforms in both the governance and sectoral legal frameworks as well as market structures.

Sector and governance reforms of state-owned enterprises: Two pieces of the same puzzle

SOE governance, sectoral policies and market reforms are closely related. The notion of sectoral reforms refers to changes made in an industry or market – frequently with heavy state participation – such as the energy or transport sectors. This often includes interventions such as unbundling, setting up an independent regulator, introducing public service contracts and tariff reforms. SOE governance reforms focus on improving the management and accountability of SOEs (including through enhanced corporate governance structures) and the way these enterprises are overseen by the state as the shareholder. By combining these two types of reforms, governments can address systemic problems that affect both the quality of public services and the efficiency of SOEs. In sectors where public services are crucial, such as infrastructure, SOEs are typically used as vehicles to ensure delivery of policy and social goals in terms of development and performance.

In some cases, the borders between SOE reforms and sector reforms can be blurred and it can be hard to tell where one starts and the other finishes – especially if we are looking at an SOE with a natural monopoly in a given sector of a country. Changing something in the SOE would have an immediate impact on the whole sector and vice versa. Important synergies can be achieved by combining these policy tools and realising that the interplay between SOE governance reforms and sector reforms can be seen through several perspectives.

First, when it comes to promoting both financial and operational efficiency, SOEs often operate in sectors that are essential for the economy and society. If these enterprises are inefficient or ineffective, it can (and often does) result in lower productivity, higher costs and reduced quality of goods and services. Policy action can mitigate this risk for essential sectors and natural monopolies. In other cases, however, SOE reform could just serve to diminish the role of the state in the economy. For example, unbundling SOEs in the infrastructure sector, including the energy industry, is often a policy tool to foster private-sector participation and improve efficiency and productivity.

Second, when it comes to the relationship between SOEs and public finances, companies that do not operate effectively present a fiscal risk and can become a drain on the state budget. They may also be the reason behind inefficient allocation of state budgets. This often happens when the state subsidises the SOE because it performs a service of public importance, but without clear parameters of the quality and cost of the service provided, which translates into less funding being available for other priorities of the government. SOE privatisation can also offer an opportunity to improve the state budget by realising income and reducing liabilities. Other times, SOEs are at risk of becoming a vehicle for political or populist goals – for example, when a certain good or service is supplied below cost recovery, thus hampering market competition and ultimately the economic development of the country, or when the SOE is used for clientelism.

Important synergies can be achieved by combining these policy tools and realising that the interplay between state-owned enterprise governance reforms and sector reforms can be seen through several perspectives.

It is therefore in the government’s own interest to ensure that SOEs deliver on what is expected of them and do so in the most efficient manner possible. Here, sector reform can be helpful in strictly defining the nature and quality of the services to be provided by the SOE in the form of a public service obligation or different performance contracts, which are costed according to a methodology agreed between the SOE and the state and which then become a contractual obligation of the SOE to the state. This helps to clarify expectations from the company and also provides transparency on the actual cost to the government for requiring these services. In case of deviations from the defined targets, it is easier to distinguish justifiable deviations from mismanagement or even corruption, thereby strengthening the accountability of the SOE’s decision-makers.

On the other hand, the state may look at profitable SOEs as a source of revenue for the state budget. While this is legitimate, it is also very important that any potential dividends from the SOE are considered within a broader context and that the company’s profit can – to the extent needed – be used for its further growth and development, which includes contributing towards meeting sectoral objectives. For example, a profitable energy company that depends on coal should certainly be encouraged, if not expected, to use part of its profits to decrease its carbon footprint. This is why it is important to have clearly defined dividend policies that take all of these considerations into account and that are also aligned with the SOE’s strategy and investment plans.

It is important to have clearly defined dividend policies that take all of these considerations into account and that are also aligned with the state-owned enterprise’s strategy and investment plans.

The EBRD’s work to strengthen sector regulation and state-owned enterprise governance

The EBRD has a long record of investment and policy dialogue in key sectors across economies where it invests, as well as supporting SOE company-level transformations. This is also recognised by the EBRD Strategic and Capital Framework 2020-25,44 which defines “stepping up support for commercialisation of SOEs in countries with potential for privatisation” as a priority action and in numerous EBRD country strategies.45

This is why the Bank developed a new technical cooperation programme called SOEs Management Assistance Reform and Transformation (SMART). The programme is designed to help the EBRD provide the most appropriate and tailored policy advice to support delivery of strategic transactions with states or SOEs combining governance and sector reforms.

The SMART programme includes support measures that can be undertaken on three levels. First, upstream reform support of SOEs’ governance envisages engagement with the state and individual authorities as owners of SOEs, with the aim of improving broader rules governing SOEs such as laws, regulations and standards, as well as building an institutional framework and capacity for overseeing SOEs and setting clear objectives by the ownership function. One level below, on the sector level, the programme envisages support for regulatory improvements that can consist of the redesign of the governance architecture for the sector, amendments to sectoral laws and regulations, development of various tariff methodologies, contractual arrangements between sectoral actors, unbundling, as well as institutional reform and capacity building to sectoral regulators.

The third possible level of intervention is at the level of SOEs themselves. Here, the measures may include corporate governance action plans – tailored plans to improve corporate governance structures and practices at SOEs – as well as corporate development programmes that go beyond the governance structures of the SOE and aim to improve its operational and financial efficiency, strategic and business planning processes, and asset management, and support necessary organisational restructuring within the SOE.

Finally, as a component that underpins these three levels of engagement, the programme also includes various state, sectoral and SOE-level diagnostic engagements. These are meant to provide the Bank with an understanding of relevant rules, practices and challenges on the ground and inform further policy interventions so the reform needs of economies and clients can be answered effectively.

By providing this targeted programme, the EBRD aims to accelerate the mobilisation of resources and be able to react more quickly to appetite for reforms that are complementary to the Bank’s financing. In addition, by being able to cover more areas within a single reform package, the EBRD can also bring focused interventions and leverage on the work of other international financial institutions.

By providing this targeted programme, the EBRD aims to accelerate the mobilisation of resources and be able to react more quickly to appetite for reforms that are complementary to the Bank’s financing.

SMART for Ukraine: Assistance where it’s needed most

In addition to the horrific human cost of the invasion, Ukraine also faces unprecedented financial and economic costs. The recent Ukraine Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment report,46 prepared jointly by the government of Ukraine, the United Nations, the European Commission and the World Bank, estimates the total reconstruction and recovery needs at US$ 411 billion as of 24 February 2023. The report also estimates the implementation priorities for 2023 alone amount to US$ 14 billion, with a primary focus on the most urgent needs such as energy, housing, and critical and social infrastructure.

Following the EBRD’s ambition to commit up to €3 billion in 2022 and 2023 to help Ukraine’s economy continue functioning, the SMART programme was designed to include a specific set of actions in addition to the ones mentioned above, to assist with the wartime resilience of Ukrainian SOEs as well as their contribution to reconstruction efforts. The possible reform interventions here therefore include support to the companies and/or ministry with war-time crisis response and recovery – such as resilience and recovery needs assessment, planning and management of supply chain, logistics, workforce and assets in the wartime and recovery context, support for cyber security, debt and risk management and contingency planning, measures aimed at facilitating procurement in both emergency and recovery contexts as well as integrity support and anti-corruption measures to ensure funds are used for the purposes for which they were intended.

SMART for Ukraine was inspired by EBRD assistance to Ukravtodor, the national road agency with core procurement functions and anti-corruption reforms. First initiated on the back of a loan signed in 2020, these reforms took on a whole new meaning when Ukravtodor was transformed into the State Agency for Restoration and Development of Infrastructure in January 2023. Further policy assistance may be deployed to help the government build anti-corruption and compliance capacity in other core SOEs, including Ukrainian Railways, and to train board directors to oversee SOE activities meaningfully and independently. This builds nicely on the EBRD’s long-term involvement in the SOE reforms in Ukraine, which included the roll-out of corporate governance transformations in most of the top 10 Ukrainian SOEs and development of comprehensive amendments to the national regulatory framework for state companies.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic, followed by the energy crisis and the war in Ukraine, reminded everyone of the need to build back better, fuelling the need for both financial and policy support and highlighting the importance of the role SOEs will play in these efforts. Hence, there is a need to enable our clients (both governments and SOEs) to turn challenges into opportunities and embark on reforms that may redefine those markets for decades to come. The EBRD stands ready to support these ambitions with a balanced mix of sector and governance reforms that can help put states and SOEs on a path towards responsible and sustainable development for the benefit of our economies and their citizens.

Following the EBRD’s ambition to commit up to €3 billion in 2022 and 2023 to help Ukraine’s economy continue functioning, the SMART programme was designed to include a specific set of actions in addition to the ones mentioned above, to assist with the wartime resilience of Ukrainian state-owned enterprises as well as their contribution to reconstruction efforts.

Public-private partnerships for promoting Sustainable Development Goals

Achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) requires long term investment. PPPs can provide some of this investment by utilising private sector skills, know-how and finance to implement long-term public infrastructure projects. For longitudinal project partnerships to be attractive to private investors, there needs to be a stable and predictable legislative and regulatory framework in place for PPPs. To facilitate the development of effective PPP frameworks, the EBRD has produced the PPP Regulatory Guidelines Collection for policymakers and practitioners to use to create legal environments that are conducive to PPPs, in line with international best practice.

Need to finance the Sustainable Development Goals

The SDGs are a set of 17 goals that aim to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all by 2030. Achieving the common objectives enshrined in the SDGs – also known as the Global Goals – is a long-term endeavour, with sufficient and targeted financing being a catalyst.

The value of capitalising on private sector financing for the SDGs has been recognised since 2015 in the United Nations Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development. It was further highlighted in the document From Billions to Trillions: Transforming Development Finance Post-2015 Financing for Development: Multilateral Development Finance prepared jointly by the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the EBRD, the European Investment Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, the IMF and the World Bank.

The private sector plays a key role in implementing the SDGs, particularly SDG 17 (partnerships), with the expectation that it will contribute with capital investment in the face of dwindling public resources. In recent years, PPPs have become increasingly important as governments around the world seek to address the immense challenges associated with pandemics, population growth, climate change and economic inequality. PPPs play a vital role in efforts to identify and implement new and cost-effective solutions by bringing together the resources of the public sector and the creative thinking, efficiency, modern technology and expertise of the private sector.

The role of PPPs in fostering sustainable development

The World Commission on Environment and Development’s 1987 Brundtland Commission report Our Common Future defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. From this definition, the inter-temporal element of development becomes clear. PPPs as instruments and financial structures encompass a long-term nature that typically includes, importantly, a servicing element. Therefore, this unique characteristic allows effective and sustainability-aligned changes to take place in the long run.

PPPs have many benefits. When properly structured and implemented, PPPs can fulfil a range of valuable purposes and objectives for the benefit of society and the common good. They can advance the efficient and cost-effective development, provision and operation of public infrastructure and public services, by harnessing the skills, resources, know-how and/or finance of the private sector most effectively and sustainably on a long-term basis, and structuring projects in ways that allocate the risks and responsibilities involved most appropriately over the project’s duration. This can strengthen the efficacy of project delivery (whether of design, construction, rehabilitation, operation and/or maintenance), stimulate new funding and investment opportunities, help bridge the public infrastructure and service gap, raise the quality of public services, improve the public’s access to those services, and so help to achieve wider economic, environmental and social goals.

PPP structure can help foster economic growth and social development in ways that promote the SDGs, leading to a better and more sustainable future for all. By bringing together different stakeholders, PPPs can create efficiencies, increase access to capital and promote innovation. Furthermore, they can help create a long-term framework for sustainability, as public and private entities work together to ensure the success of their projects, becoming more prevalent in the sustainability realm. As governments around the world recognise the importance of private sector involvement to achieve the SDGs, there has been an increase in the number of PPPs and the scope of their projects. In a similar vein, the EBRD has been actively working to help governments develop legal and regulatory frameworks for PPPs in a good number of countries in its regions. This has enabled governments to better leverage the resources of the private sector in developing sustainable projects that benefit local communities.

In a similar vein, adequate and well-allocated financing is a critical enabler for the development and the success of a PPP, which in turn will advance the host country’s development agenda. To this end, the Bank recently commissioned a study on the sources and types of financing for PPPs in the EBRD regions. In the context of global financial and economic instability, many countries are experiencing difficulties in financing infrastructure projects, especially large-scale ones. Similar to the identification of alternative mechanisms and processes to achieve sustainable development (for instance, turn to renewable energy and responsive financial regulation), diversification of financing sources for PPPs is most welcome.

Looking beyond traditional bank lending, there is room to explore alternative ways to finance PPP projects. Global awareness of sustainable PPP projects has grown among institutional investors, especially as governments have been trying to scale up investments to meet the SDGs. Introducing innovative financing and new forms of PPP structures could offer a broader range of PPP financing mechanisms, which could better address the needs and financing/funding gaps in so many jurisdictions. Indicatively, alternative types of financing might include blended finance and receivables financing and alternative sources of financing might include pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and impact investors. In a nutshell, alternative means of PPP financing shall be explored as they are of great importance for supporting the viability of SDG-oriented projects.

PPP structure can help foster economic growth and social development in ways that promote the Sustainable Development Goals, leading to a better and more sustainable future for all.

PPP legal frameworks

Sound PPP legal frameworks and policies are of paramount importance for the PPP sector’s development. A stable and predictable legislative and regulatory environment makes it easier to attract investment in PPP projects and further lays the ground for the successful completion of PPPs.

Until recently, almost all PPP legal frameworks primarily focused on commercial business practices, which, to an extent, would ensure the commercial viability of the project. While the actual objective of the project may have been society-oriented or environmental in nature (healthcare or education social infrastructure projects, for instance), the focus of the legal framework was geared towards the mechanics of the project per se and aimed at enhancing well-recognised legal values, such as transparency, predictability and accountability.

In line with the global shift towards proactively infusing sustainability considerations in legal and regulatory texts and policies, the EBRD’s work on PPPs has been critical in helping develop and implement the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. The Bank has provided technical cooperation to its economies to help them identify and implement projects that reduce emissions and promote renewable energy sources. This has included activities such as developing legal and regulatory frameworks for PPPs, providing capacity building to local stakeholders and facilitating access to finance for green projects.

Most importantly, the EBRD has developed a collection of PPP regulatory guidelines over the past few years that represents some five years of hard work by a dedicated group of experts, most of whom took an active part in this formidable effort on a pro bono basis. The publication aims to address the needs of the many governments and authorities in the EBRD economies that shared their feedback and priorities with the EBRD regarding their desire and even the necessity to assemble examples of internationally accepted standards and best practices in the area of PPPs as far as its regulatory, institutional and enabling frameworks are concerned.

The EBRD Legal Transition Team has carried out PPP regulatory advisory technical cooperation projects in more than 30 countries, helping to upgrade a legislative and/or enabling framework or institutional infrastructure, and to enhance the public sector’s PPP capacity. By way of example, the team has provided a comprehensive programme of technical cooperation to the Serbian authorities since 2011. Serbia is one of a very few countries where the Bank exercised a well-structured approach, from helping the authorities design and draft PPP policy to drafting PPP law, creating regulatory and institutional frameworks and an enabling environment, and offering training in the country’s regional centres. This contributed to the development of a good number of banking projects. The Bank used an integrated approach in Serbia and coordinated with the EBRD Banking Department on regulatory framework advisory, which helped identify gaps and room for improvement (the Bank then considered Belgrade underground parking and a number of other potential municipal and transport infrastructure investments). As a result, within three years of the new law’s enactment, the pipeline of PPP projects grew significantly, from just a handful to more than 50, and Serbia’s PPP programme keeps expanding.

A stable and predictable legislative and regulatory environment makes it easier to attract investment in PPP projects and further lays the ground for the successful completion of PPPs.

THE EBRD’s PPP Regulatory Guidelines Collection

The EBRD’s PPP Regulatory Guidelines Collection (hereinafter the EBRD PPP Guidelines) is a nearly comprehensive massive resource for policymakers and practitioners involved in developing and implementing PPP projects. The collection offers guidance on the key legal, regulatory and contractual aspects of PPPs, including PPP policy formulation and law drafting, key elements of the PPP regime, procurement, risk allocation, project appraisal and monitoring and dispute resolution. It is based on the EBRD’s extensive experience with both regulatory advisory and supporting PPP projects across its regions of operation, and reflects internationally recognised standards and best practices. The collection is a valuable tool for governments seeking to promote private sector participation in infrastructure development and for private sector stakeholders looking to navigate through the complexities of PPPs. By providing a clear and practical enabling framework for developing PPP projects, the EBRD PPP Guidelines can help to promote transparency, accountability and good governance in infrastructure development, and can contribute to the sustainable development of economies. The publication consists of three volumes and will be issued as an electronic version and in a limited number of hard copies.

The EBRD PPP Guidelines consist of a set of model laws, policies, explanatory materials and templates that have been produced according to best practices and can be used by governments as benchmark and reference material.

Central to Volume I of the guidelines is the EBRD/UNECE Model PPP Law for SDG-compliant PPP Projects (the Model Law). The Model Law was drawn up as part of the wide-ranging corpus of guidance documents, modules and studies on PPPs being produced on behalf of both the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Working Party on PPPs and the LTP of the EBRD to help governments seeking to develop PPP systems of their own – both those doing so for the first time and those willing to upgrade their own regime.

The Model Law is followed by a supporting commentary that narrates short summaries of the Law’s articles and provisions and provides brief explanations of the thinking behind them and some discussion of the core issues to which they typically give rise in practice. The commentary, written in non-legal language, offers some additional elucidation of the Law’s text and where it might be helpful, but does not attempt to restate or explain every one of its provisions.

Similarly, parts of the EBRD PPP Guidelines are devoted to six modules/chapters containing notes on regulations and guidelines to support the Model Law. These guidance notes are designed to show governments, regulators, PPP units and others involved in developing or refining the subsidiary documents that often support and accompany PPP laws how to prepare and draft them. Supporting documents of this kind will typically fall into two broad categories, namely regulations and guidelines. Both are defined in the Model Law, the former being designed as legally binding secondary legislation, covering the detailed procedures and mechanisms necessary to give effect to a PPP Law, the latter as guidance texts that describe, explain and advise on their application.

The EBRD PPP Guidelines are an essential resource for policymakers, legal practitioners and investors involved in PPP projects.

The guidance notes cover six main categories that represent the areas where the supporting documents are likely to have their principal focus. These are: PPP criteria and requirements; forms of government support; tendering procedures and requirements; unsolicited proposals and direct negotiations; appraisal and approval procedures; and review and challenge procedures.

Volume I also includes the CIS Model Law on PPPs, adopted by the Inter-Parliamentary Assembly of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS IPA) in 2014. This model law serves as a guiding framework for PPP projects in the CIS region, providing legal and regulatory guidance on all aspects of PPPs. It aims to promote the adoption of best practices and standardisation across the region. The model law includes provisions on project preparation and selection, procurement, contract management and dispute resolution, among others. It is the first comprehensive text of PPP model laws that could be used with (or even without) adjustments and national specifics additions by CIS countries, given the common legal systems background and similarities in emerging economies development. The CIS IPA has adopted several enabling regulations and documents to support its implementation. These include Guidelines for the Preparation and Implementation of PPP Projects, the Model PPP Contract and Guidelines for the Development of PPP Legislation at the National Level. These documents, as well as the CIS Model PPP Law itself, were developed with the EBRD’s assistance. They provide detailed guidance on the practical implementation of the CIS Model Law, including the key steps and processes involved in preparing and implementing PPP projects. These enabling regulations and guidelines will be part of Volume II of the EBRD PPP Guidelines Collection.

The EBRD recently participated in the seventh UNECE International PPP Forum in Athens. The 3-5 May 2023 event brought together more than 700 participants from around the world, including policymakers, practitioners and experts in the field of PPPs. One of the highlights was the EBRD session specifically dedicated to the presentation of its PPP Regulatory Guidelines Collection. The forum provided an important platform for stakeholders in the field of PPPs to exchange ideas and best practices, and the EBRD’s participation and presentation of the publication underscored its commitment to promoting good governance and sustainable development in infrastructure investment.

The EBRD PPP Guidelines are an essential resource for policymakers, legal practitioners and investors involved in PPP projects. The collection is available on the EBRD LTP web page (www.ebrd.com/law). The web page, which is accessible to all visitors to the EBRD website, hosts a variety of legal resources, including publications, research and reports on various legal subjects. For more than 25 years, PPP support has been a core part of the EBRD LTP designed to provide regulatory and institutional support to authorities in the EBRD regions and help them create an enabling environment in a few carefully selected areas of important commercial law. Working with colleagues in the Banking and Policy departments’ advisory on regulatory aspects of PPP has always been an integral part of EBRD undertakings. The SDGs have become the central focus and will remain such in the foreseeable future.

Are you ready for online courts?

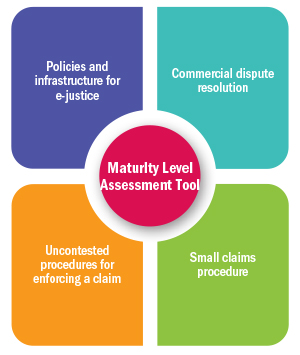

The idea of leveraging technology to streamline and improve the delivery of justice has been gaining traction. In the area of commercial justice, developing online courts can ease access to justice for SMEs and provide fast, cost-effective and efficient resolution of their cases in courts. The Legal Transition Programme has recently focused on promoting the development of online small claims courts in the EBRD regions, and in 2022-23 assessed the extent to which the regions are ready to introduce, or have already developed, online courts. This article presents the findings from 17 economies where the EBRD operates.47

Introduction